From Watchers to Catchers

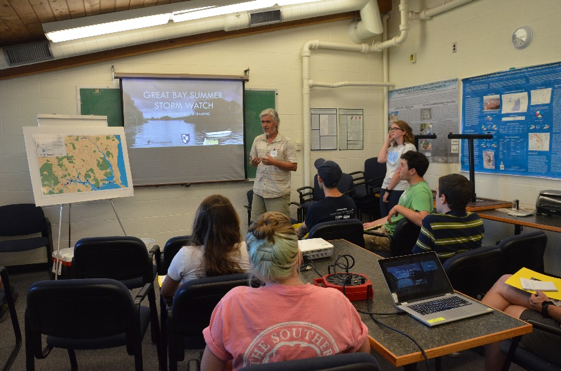

For those that have read my bio or taken a look at my story “Keeping the Great in the Great Bay,” you’ll know that my project this summer has been to plan a volunteer citizen science project to track and capture water samples and data from two storm events in the month of July. On June 30th our team of interns, staff, and professors working on this research project in the Great Bay held a UNH Storm Watchers’ Training. A group of eight passionate and enthusiastic volunteers from New Hampshire towns and cities came and learned about the Great Bay Summer Storm Watch. We taught them about the project as a whole, storm safety, the various sampling sites, how to use a conductivity meter and most importantly how to take a water samples. The volunteers asked many great questions and after the training was finished all we could do was hope for a big storm to come our way.

The month of June had been so dry that our team was worried that we wouldn’t get a storm big enough to have an impact on the watershed. Within a week of the training however, several weather stations began to predict a big storm coming our way. The team quickly shifted into gear, making phone calls to volunteers, deploying auto sampling machines at the hard to reach sites, and getting ready to assist with storm sampling. Everything came together on the weekend of July 9th – 10th when the volunteers went out and collected samples from Oyster River (Durham, NH), Beard’s Creek (Durham, NH), and the Bellamy River (Dover, NH). Our team of interns then retrieved the samples and stored them in the lab to await processing. Overall, the weekend went very smoothly. I was amazed at the hard work and dedication of the volunteers, they truly showed that they cared about this project as much as the professors, staff and interns. They were willing to work hard to ensure that the samples were taken effectively and on time throughout the course of the storm. In the end, a total of thirty six water samples were taken at three sites by the eight volunteers and four interns.

After the storm, interns Emily Balcom and Christine Bunyon began work on filtering the samples taken by the volunteers and auto sampling machines. Emily worked out of a UNH laboratory to process samples and then dry and weigh filters to determine the amount of suspended sediments in each sample. Levels of suspended sediments may be linked to levels of bacterial contamination, so this was an important part of the data collection. In addition, Emily began work on analyzing the connections between watershed size and presence/absence of a reservoir on the levels of bacterial contamination. Christine worked on bacteria filtration at Jackson Estuarine Laboratory where she filtered each sample, put the filters onto growth plates, and incubated them for 24 hours before counting the number of bacteria colonies on each plate. Christine then performed identification of bacteria colonies by using Microbial Source Tracking (MST) to determine the types of DNA present in the bacteria. Determining the source of the contamination can improve management of watersheds by targeting specific areas in need of improvement.

The complete findings from this project will include analysis of all of these factors in order to gain a better idea of where the contamination is coming from and how it is transmitted into the Great Bay and beyond. As the project wraps up, the final samples are being run and the data is being compiled. It will be some time before the official report is released, but we hope that the findings from this study will encourage better care and management of the Great bay and its watershed by local governments, interest groups, and stewardship organizations. The first step to better management is better understanding, and this project has taken great strides towards understanding the effects that various factors have on bacterial contamination within the Bay.

I want to take a moment to thank all of the volunteers that helped with the storm sampling. They did phenomenal work and I was truly amazed by their enthusiasm and dedication to the project! It occurred to me afterwards just how exceptional these citizen scientists were. While most people probably saw the forecast and canceled their cookouts and trips to the zoo, these volunteers geared up to get wet and do research. The data they collected will add a whole new dimension to this research that would not have been possible without their contribution. This additional data will allow for a better understanding of what goes on in the Bay during less than optimal sampling conditions. The impact they made was very real and will make a great starting point for future research in the Great Bay!

If you want to check out more projects like this one and engage with some of the Stewardship Network: New England’s amazing volunteers, I encourage you to check out the calendar and sign up for an upcoming event! You’re sure to meet some great people and have a fun day of volunteering for nature.