Undergraduate Students Lead Volunteer Storm Watchers in Water Quality Investigation

Keeping the "Great" in Great Bay

What do citizen scientists, storms, oysters and an estuary have in common?

Five interns.

Students at the University of New Hampshire teamed up this summer to help protect Great Bay and its burgeoning oyster industry.

Shellfish culture brings both economic and environmental benefits—a win win for oyster farmers. And as local raw bars grow in popularity, more of the meaty bivalves farmed in Great Bay are being devoured by seacoast patrons. Unfortunately, water pollution and rising temperatures threaten this fragile resource, as do tensions about public health threats and shellfish closures for regulators, shellfish harvesters and business owners.

According to NH Dept. of Environmental Services, the most common cause for shellfish bed closures is rain from high levels of bacteria entering the water.

So what can citizen scientists and student interns do?

The interns, participating in a summer research experience for undergraduates, worked with scientists from NH EPSCoR’s Safe Beaches and Shellfish project funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The team seeks opportunities to strengthen the connections between coastal business communities and resource managers.

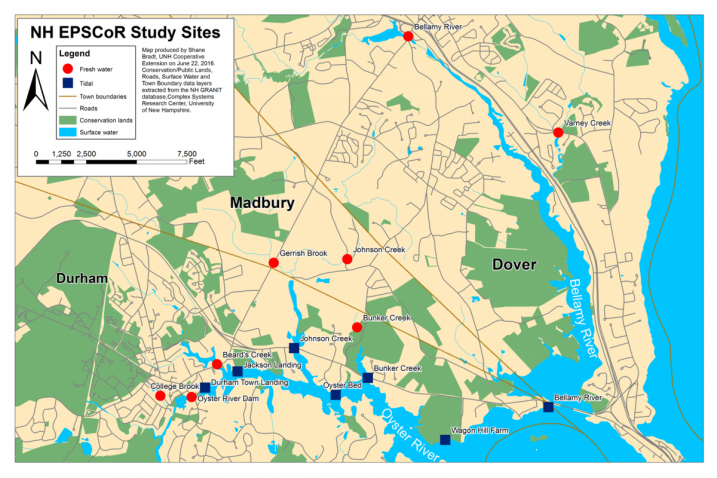

Sophomore Emily Balcom, an environmental engineering major, examined tributaries where bacterial contamination from freshwater can enter Great Bay and potentially affect the use of shellfish grown there. She worked with faculty mentor Wil Wollheim, associate professor in the Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment and Earth Systems Research Center at UNH.

Junior Christine Bunyon, an environmental conservation and sustainability major, investigated shellfish harvesting locations and worked with Steve Jones, research associate professor in the Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment. Bunyon was able to use analysis of DNA genes to identify which animal sources within the watershed were contributing to contamination in the Oyster River.

“Emily and Christine did an excellent job planning and executing the study,” said Wollheim. “The information they collected can be used to better prioritize management activities that reduce bacteria contaminants.”

Two samples were collected by UNH junior Christine Bunyon at the estuarine sites shown on the map in dark blue (one for total suspended sediment analysis and one for bacterial analysis) and measured dissolved oxygen, temperature, and salinity. Sophomore Emily Balcom sampled freshwater sites shown on the map in red.

All five interns helped Balcom and Bunyon collect water quality samples during dry weather. But the study really needed rain data during peak water flows because much more contamination occurs during storms. This information would be very difficult for the research team to gather alone.

As soon as freshman classes ended, environmental engineering major Megan Verfaillie started recruiting volunteers. It’s hard to predict exactly when it’s going to storm, so the team needed dedicated ‘on-call’ participants. She worked with mentor Malin Clyde, UNH Cooperative Extension Specialist, to utilize the Stewardship Network: New England and found eight eager citizen scientists they dubbed “Storm Watchers.”

Together the students led the volunteers through water collection training, safety, presented background information on the larger NSF project, and demonstrated how samples would be analyzed in the lab.

The volunteers, in addition to helping collect valuable research data, learned more about threats to Great Bay and local shellfish farmers.

"The interns had really strong communication and collaboration skills, and they were excited about involving the community around Great Bay in the UNH research. We didn’t show them how to do this interdisciplinary work, they just did it,” said Clyde. “To me, that’s very encouraging for the future of environmental science!”

Finally, after an excruciatingly dry summer, in the middle of the night interns were calling volunteers to grab their rain gear and move out. Over the course of a July storm (in six different locations simultaneously) thirty-six storm water samples were gathered for research.

“It taught me a lot about how much detail goes into planning events,” said Verfaillie about the project. “I hope that in my future career, I will be able to continue to incorporate citizen science into my field of engineering.”

Now that the research team has collected all of this information about Great Bay, what is the best way for it to get communicated to the people who can use it?

Junior Jess Hillburn, a mathematics major, and junior Maddy Webb, a sociology major, conducted interviews over the summer with local officials, restaurant owners, and oyster farmers. They were guided by Tom Safford, a sociologist at UNH, and graduate students examining oysters as a food source.

“Through these interviews we are seeking to better understand stakeholder perspectives on water quality and the use of science.” said Lindsey Williams, a PhD student working with Safford who helped mentor Hillburn and Webb through the interview process.

By canvassing the major players in the shellfish community the team can learn more about how information gets communicated and how businesses are affected by closures or issues with water quality.

“Our project was a collaborative effort between different branches of science and I’ve since become a huge advocate for interdisciplinary research. Something I hope to continue in the future,” said Webb about her summer research experience at UNH with NH EPSCoR.

Make the system better, connect science to communities and decision making, increase our knowledge and economic prosperity—that’s what undergraduate researchers and citizen scientists can do.