Crowdsourcing Storm Damage to Trails

The 2017 Halloween Storm event took the White Mountain National Forest by surprise. The end of October is usually a welcome lull after the busy summer season and as fall foliage wraps up. For permanent Forest Service employees, it is a time of reflection on the previous season, end of year reporting, and anxiously awaiting the arrival of the new fiscal year’s budget. Most of our field-based seasonal staff are laid off at the end of September. This is especially true for members of our backcountry and trail crews. The late October storm hit when we had a handful of seasonal staff (held for rehab work on the Dilly Fire) and 1600 miles of trail to survey before winter settled in. With rainfall and winds that exceeded Hurricane Irene levels in some areas, we knew we wouldn’t make it alone. Before snow fall, many partners and volunteers came together to help the Forest Service survey approximately 1200 miles of trail and track damage using an online GIS map (no longer available to the public).

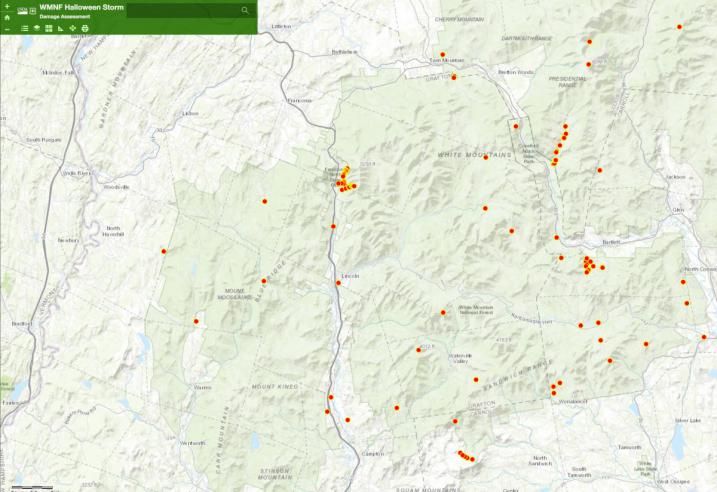

We were able to make good use of our partners, volunteers, and interested members of the public through an online data collection portal called Survey123 for ArcGIS. Thanks to Forest Service GIS Specialist Anna Johnston’s initiative, this technology allowed people outside of the Forest Service to report damage with photos and descriptions in real time directly from their cell phones. These data points were aggregated on a public facing map. Anyone could track the survey status of their favorite trail and Forest Service employees had instant access to geospatial and digital damage reports. With real time reports coming in from over 100 surveyors, 75% of the surveyed miles were completed by non-Forest Service employees.

The Forest’s request for help from the public was widely cast in social media, local news outlets, and on partner websites like Nature Groupie. It is a testament to the volunteer spirit in the region that so many interested people answered the call. This technology represents a giant leap forward in the public’s ability to interact and impact management on their public lands. With a more refined protocol and some additional training, I expect this technology will become a huge part of how the WMNF trail program receives and responds to information from the public.