Searching for Pellets at the Bunny Blitz

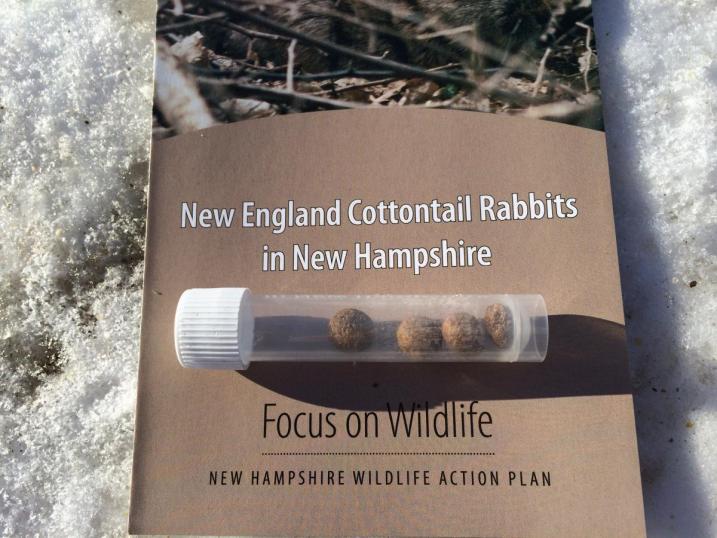

Christine Caprio, Bob Basile, Emma Carcagno, and Siobhan Basile (from left to right) collected rabbit or hare pellets from the Deer Hill Wildlife Management Area in Brentwood. Only DNA analysis can determine whether these are from New England cottontail, eastern cottontail, or snowshoe hare.

Volunteers in the seacoast and Merrimack Valley of New Hampshire are snowshoeing along field and wetland edges and crawling into dense brush looking for rabbit pellets.

The eastern cottontail rabbit was introduced into New England to improve hunting opportunities in the early 1900s and is now the dominant rabbit in New Hampshire. Unlike the native, state-endangered New England cottontail, eastern cottontails are better able to survive in fragmented, human dominated landscapes. Meanwhile, the range of our native rabbit, the New England cottontail, has shrunk by more than 85%. The other “rabbit” is the relatively common and much larger snowshoe hare, which turns white in winter. Both cottontails remain brown year-round.

The two rabbits look nearly identical. The eastern cottontail is a little bigger with slightly larger ears and eyes—small differences that make it hard to differentiate in the field. And their pellets look the same. Only through DNA analysis of the rabbit droppings can biologists separate the species. Collecting pellets in southern New Hampshire, where the two species overlap, will help biologists understand where eastern cottontails occur, their abundance, and potential threats to New England cottontails.

Since pellet surveys are intensive and the area to search is large, UNH Cooperative Extension and NH Fish and Game hosted a Bunny Blitz to train and inspire volunteers to help with the search. Twenty-five enthusiastic people from 11 towns met at the Rockingham County Complex in Brentwood, NH on a brisk, sunny winter day to learn about cottontails and look for rabbit pellets.

With a cold wind blowing, volunteers stood in a large circle as Heidi Holman, Fish and Game biologist and project coordinator for New England cottontail recovery, described the two rabbits and how to search for and collect pellets. After a brief snowshoe to look at typical rabbit habitat—dense shrub thickets—we split up into small groups, data sheet and collection protocol in hand, and headed out to potential rabbit sites in Brentwood.

This winter has been tough on rabbits. New England cottontails need dense cover to find food, raise young, survive winter, and escape from predators. A lot of shrub thickets are now buried in deep snows, increasing the likelihood that rabbits have been exposed to high predation rates by coyotes, foxes, fishers, bobcats, and owls.

After a few hours of searching selected sites, volunteers returned to share findings and enjoy hot chocolate. One team found pellets, receiving the prize of a large chocolate bunny. We won’t know what species until the DNA analysis is completed. Although most groups didn’t find any sign of rabbits, there was plenty of wildlife drama to see in the snow: bobcat tracks across a brook, red-tailed hawk wing prints in a field where it captured meadow voles, a bounding deer, squirrel tracks, and turkey prints.

To join in the search for rabbit pellets—more volunteers are welcome—contact Haley Andreozzi, UNH Cooperative Extension, Wildlife Program Outreach Coordinator. There is still time to look for rabbit droppings given the persistent snow cover this winter.